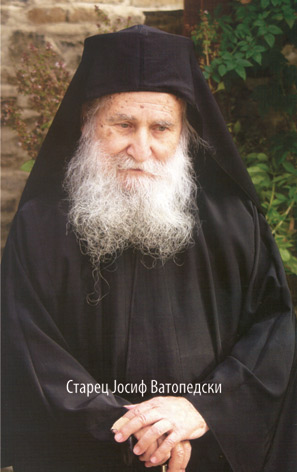

Elder Joseph of Vatopaidi

(

07.02.2009

)

Our life with the Elder had the character of childhood rather than a mature state. Our effort, in basic terms, was directed towards the monastic tradition, and we exerted ourselves as forcibly as possible in the obligations of our rule. What we lacked, essentially, was the discernment gained through experience in discrimination; this would have enabled us to evaluate the situation, so that the spiritual dimensions of the Elder would not elude us in their depth and breadth and height. But is it not perhaps usual and inevitable for disciples to discover their teacher only 'when he is taken from them’? (cf. Lk. 24:31). Untiringly, the Elder made a constant effort to pass on everything to us that is spiritual and he did not fail in his aim, because 'the wise man has his eyes in his head' (Eccl. 2:14). It is true, however, that 'for everything there is a season, and a time for every matter' (Eccl. 3:1).

At a mature age, when the Elder was no longer with us, we understood the depth of his words and his actions even down to the details, whereas while he lived they seemed, to our inexperience, riddles that made no sense. We put all our meagre powers into our effort to be obedient and not to grieve the Elder. But we had virtually no comprehension of the meaning and main aim of the spiritual law which the Elder passed on to us with such fervour. I will not go into biographical details again, but I want to comment a little on the aforementioned subject of the spiritual law, which is what chiefly governs human beings.

We observed that the Elder never embarked on anything without first praying. We would ask him about something in the future or for the next day, and his reply was that he would tell us tomorrow. He would do this so that he could pray first.

Our desire focused on knowledge of the divine will: how should one recognise the divine will? He would say, 'Are you asking about this, boys, when it is the most basic thing?' We would encourage him with increased curiosity, 'But, Elder, isn't God's will known in general terms through the Scriptures and the whole of divine revelation? Since everything in our life is regulated, what other question should we monks have?’ And the Elder replied, 'May God give you "understanding in everything" (2 Tim. 2:7). St Nilus the Calabrian prayed that he might be granted "to think and speak according to the divine will". In general terms, to do good and every other commandment is the will of God, but the detail which governs it is unknown. "For who has known the mind of the Lord?" (Rom. 11:34); and again, "the judgements of the Lord are a great abyss" (Ps. 36:6). The divine will is not differentiated only by time, but also by place, persons and things, as also by quantity, manner and circumstance. And is that all? Man himself, when he changes his disposition, also changes the divine decision in many ways. So it is not enough to know the general expression of the divine will; one needs to know the specific verdict on the subject in question, whether yes or no, and only thus is success assured. The chief aim of the divine will is the expression and manifestation of divine love, because the driving force of all our actions is precisely the fullness of His love. If "whether we live or whether we die, we are the Lord's" (Rom. 14:8), as St Paul says, then, however much the will we are seeking seems to be personal to us or to someone close to us, its centre of gravity is the Divine Person, for whose sake "we live and move and have our being" (cf. Acts 17:28). Have you forgotten the Lord's prayer in the

'So when you want to find out the will of God, abandon your own will completely together with every other thought or plan, and with great humility ask for this knowledge in prayer. And whatever takes shape or carries weight in your heart, do it, and it will be according to God's will. Those who have greater boldness and practice in praying for this will hear a clearer assurance within them, and will become more careful in their lives not to do anything without divine assurance.

'There is also another way of discovering the will of God which the Church uses generally, and that is advice through spiritual fathers or confessors. The great blessing of obedience which beneficently overshadows those who esteem it becomes for them knowledge where they are ignorant and protection and strength to carry out the advice or commandment, because God is revealed to those who are obedient in His character as a father. The perfection of obedience, as the consummate virtue, puts its followers on a level with the Son of God, who became "obedient... unto the cross" (Phil. 2:8). And as our Jesus was given all power (Mt. 28:18) and all the good pleasure of the Father, so the obedient are given assurance of the divine will and the grace to carry it out successfully and to the full.

‘Those who ask spiritual people in order to discover the divine will should be aware of this point: the will of God is not revealed magically, nor does it hold a position of relativity, since it is not contained within the narrow confines of human reason. In His consummate goodness God condescends to human weakness and gives man sure knowledge. But man must first believe absolutely, and secondly humble himself by thirsting ardently for this assurance and by being disposed to carry it out. This is why he receives with faith and gratitude the first word of the spiritual father who is advising him. When, however, these requirements of faith, obedience and humility do not co-exist - and it is a sign of this when someone objects or counters with other questions, or worst of all has a mind to keep asking for second opinions - then the will of God is hidden, like the sun behind a passing cloud. This is a subtle matter, and requires great care. Abba Mark says, "A man gives advice to his neighbour according to what he knows; but God works in the hearer according to his faith." An essential requirement in seeking the divine will is that the person who is asking should make himself receptive to this Revelation, because, as I have said before, the divine will with its transcendent character is not magically contained within positions or places or instruments, but is revealed only to those who are worthy of this divine condescension.’

I am reminded now what happened with us, when we asked the Elder to tell us the will of God. We had got into the habit from previous experience and received as absolute his first word, without contradiction; and indeed everything happened just as we would have wished, even in cases where the thing did not seem to make good sense humanly speaking. We knew that if we put forward some sort of objection on pretexts that were reasonable according to our own judgement, the Elder would give way to us, saying, 'Do as you think best'; but the mysterious power and protection of success would be lost to us. Therefore it was the 'first word' from the spiritual father, received with faith and obedience, that expressed the divine will. In its general form this subject is complex and obscure because, as we know, the divine will is not always known even to the perfect, particularly when someone wants to discover it within a limited time-frame. At other times a difficulty also arises from the state of the person who is interested, depending on how far he is free from impassioned tendencies and appetites under the influence of which he acts and makes decisions, in which case patience is also required.

I myself have heard from a spiritual man, someone altogether reliable, that he besought God to reveal His will on a question in his own personal life and received the answer he had asked for forty-two years later!

I in my slothfulness was quite taken aback, marvelling at his cast iron patience.

The general conclusion is that discernment of the divine will is one of the most delicate and complex matters in our lives. Especially for those who try to discover it through prayer - even though this is required, according to die saying 'knock, seek, ask and it will be given you' (Mt. 7:7) - it must nevertheless be preceded by patient endurance, trials and tribulations and experience so as to remove the passions and the individual will, which the exceeding subtlety and sensitivity of divine grace abhors. Anyway, whether it is arduous or whether it requires patient endurance, the method of prayer remains a requirement as the only means whereby we communicate with God, and by which we shall also know His divine will.